Post-Facilitation Reflection: Using the Community of Inquiry Framework for Online Facilitation

- Ashley Breton

- Nov 4, 2022

- 11 min read

By Ashley Breton

Written October 27, 2022

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

The past 9-weeks of LRNT528 Facilitating in Digital Environments course at Royal Roads University have been all about examining teaching and learning in online environments using the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework.

For our capstone project, four teams of four collaborated to design, develop, and deliver a week-long facilitation experience on a topic of their choice using the CoI framework to guide our decision-making.

My team (Ash Senini, Emma Keating, Karen McMurray, and myself), a group made up of education professionals with different backgrounds and skills, presented a course from October 9th until October 15th, 2022, on Open Educational Practices (OEP) for online facilitation.

The following reflection is based on my team’s facilitation experience. It aims to explore our design process, reflect on peer feedback, and identify lessons learned to encourage improvement in best practices for future projects. Embedded within this reflection are materials used to organize and design our course.

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

The Design Process

This section is about better understanding our design process and the goals and objectives of our facilitation week.

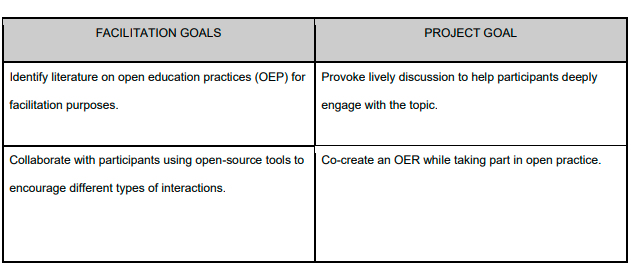

Planning. Our first step was to schedule an initial meeting to discuss what topic we would like to present for our primarily asynchronous online course, oriented towards working adult students. The four of us met over Zoom and selected OEP and how the move to ‘open’ might change the role of the online facilitator. Cronin (2017) defines OEP as a broad term used to describe “collaborative practices that include the creation, use, and reuse of OER, as well as pedagogical practices employing participatory technologies and social networks for interaction, peer-learning, knowledge creation, and empowerment of learners (p. 18). We chose this topic because our team had a Subject Matter Expert (SME) on OEP and the rest of us felt it would be 4 an exciting topic to explore. Next, we determined our facilitation and project goals outlined in Table 1 and our project objectives listed in Table 2 using Bloom's Taxonomy.

Table 1.

Facilitation and project goals

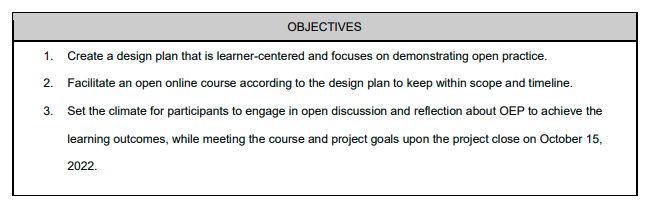

Table 2.

Project goals and objectives

Design. When it was time to start designing, our team felt it was important to demonstrate an open facilitation practice, so we designed our course on a WordPress blog (see Figure 1) to seamlessly guide our participants throughout our facilitation week while opening access to other learners on the web (Cronin, 2017). Another benefit of hosting our course on 5 WordPress was that we could provide access to all resources even after the course had finished.

Figure 1.

WordPress course website

Note: Image of the Open Educational Practices for Online Facilitation course website implemented with WordPress (https://malat-webspace.royalroads.ca/rru0212/openness-and-facilitation/).

Next, we set learning outcomes that identified what our participants needed to demonstrate upon completion of the learning experience. They were as follows:

Experience OEP through collaborative activities, curated readings, and cohort discussions using open tools.

Reflect on learnings about OEP as it relates to your practice, and share this information with others.

Once these learning outcomes had been established, we organized, sequenced, and paced course content around three main learning events:

Synchronous course introduction,

Asynchronous social annotation activity, and

Asynchronous reflection activity

These learning events were incorporated into our design plan (see Appendix A) to engage our small group of participants in different types of interactions as they moved through the course. However, the success of these activities was highly dependent on significant learner participation and interaction.

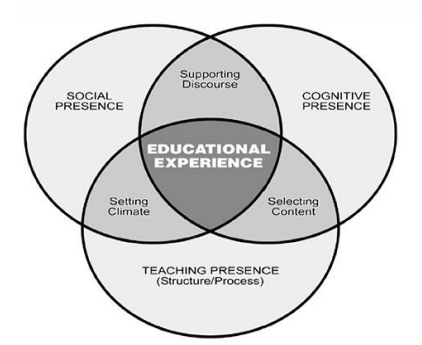

Development. During this stage, our team assigned team roles and responsibilities (see Appendix B), then worked out the details and built out the course components. We wanted our learners to have the freedom to construct and put together their own knowledge and understanding of OEP for online facilitation purposes, so as a basis for our course development, we blended principles of Adult Learning with Garrison et al.’s (2000) Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework (see Figure 2) to guide our decision-making.

Figure 2.

Community of Inquiry Framework

Note: Community of Inquiry Framework. From “Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education,” by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2000), The Internet and Higher Education, 2 (2-3), p. 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

The CoI framework includes many tenants of social constructivist theory and advocates that within online environments, the most optimal educational experience occurs when three interconnected facets — cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence — interact with one another (Anderson, 2018). In light of this, striking a balance between the presences was important for our course development because it encouraged our team to include facilitation strategies that would maximize knowledge sharing and interactions between learners, learners and course facilitators, learners and content, and learners and others on the web (Garrison et al., 2000). Attempting to create a dynamic learning experience like this required a lot of detail and involved continuously referring back to the CoI framework as our learning model. In the following paragraphs, I showcase some of the facilitation strategies we employed for each presence.

Cognitive presence. The element of the CoI model that is most basic to the success of adult learners, specifically adult learners in higher education, is cognitive presence (Akyol & Garrison, 2009). Cognitive presence is the ability to construct meaning through sustained reflection and discourse (Garrison et al., 2000). Given this, it was important to develop activities that aligned with the course learning outcomes while also providing ample opportunities for participants to construct knowledge and understanding, both as individuals and as a collective, through continuous and purposeful communication (Garrison et al., 2000). Some broad strategies that we used to encourage cognitive presence included:

Position students as the teacher. As our course was oriented towards working adult learners, our team knew we were not the only ones who knew a thing or two about OEP for facilitation. For this reason, we tried to provide ample opportunities for participants to be seen as experts by sharing their ideas and experiences with others (Garrison et al., 2000; Richardson et al., 2009, as cited in Fiock, 2020). Our asynchronous social annotation activity using Hypothes.is supported open pedagogy, which required our team to share control with our learners by giving them the responsibility to contribute to 8 the learning of others (Ehlers, 2011). This exercise aimed to facilitate interactions between learners, learners and content, and to a lesser degree, learners and course facilitators to trigger further exploration into the material as participants reviewed the annotations and conclusions of their peers (Brown & Croft, 2020). Correspondingly, a QR code was embedded in our course website that linked to an editable Google Doc with supplementary OEP resources that participants could review and add to.

Sustain discourse. The Hypothes.is exercise supported collaborative online learning using constructivist methods to avoid placing too much control in the hands of the course facilitators and to reinforce continuous opportunities for quality learner-learner interaction (Garrison et al., 2000). It also allowed learners to actively engage with an open tool as they co-created an OER and participated in open pedagogy (Brown & Croft, 2020).

Encourage reflection. Our team also placed a strong emphasis on learners developing personal meaning through reflection. Our reflection activity, positioned at the end of our facilitation week, included intentional prompts that encouraged participants to see beyond OEP and explore the applications of the material in their context (Garrison et al., 2000). These personal reflections were posted on participants’ MALAT WordPress blogs and aimed to share their learnings openly with others, while helping participants better understand themselves and the world around them concerning OEP, potentially resulting in fundamental shifts in their mindset and practice (Blaschke, 2021). We also welcomed learners to participate in an optional post-course exercise repurposed from Making Sense of Open Education by Maureen Glynn and licensed under CC BY 4.0 International, which encouraged participants to set three development goals to share on social networks using the #RRUMALAT hashtag or simply save to revisit later.

Social presence. Anderson (2018) describes social presence “as the ability to project one’s self and establish personal and purposeful relationships” (p. 63). Typically, in online environments, social presence is, for the most part, overlooked or discussed as something 9 students do or have (Anderson, 2018). However, as we understood it, the responsibility falls primarily on the shoulders of the facilitators who set the tone for the course by creating a safe space for participants to openly communicate and authentically express themselves (Garrison et al., 2000). Some broad strategies that we used to encourage social presence included:

Set the climate. In the early stages of our course, we wanted participants to feel comfortable communicating in our primarily text-based learning environment. To set the tone for our learners, we incorporated a variety of elements into our course website development, such as humour (e.g., childhood photos and funny blurbs for our facilitator introductions; Lowenthal & Dunlap, 2018), emoticons (Fiock, 2020), links to facilitators’ social networks to encourage informal relationships (Cronin, 2017), icebreakers (Fiock, 2020), and synchronous and asynchronous activities (Garrison et al., 2000). In addition, it was important for us to ensure all course activities would be kept at a level where everyone could participate, regardless of their past experience or level of expertise with the topic. We achieved this by explicitly stating that our course did not assume any prior experience with OEP for online facilitation, but encouraged those with limited knowledge to check out a short list of curated resources.

Build community. To establish community immediately, our team sent out a welcome email on Day 1 of our facilitation week to provide participants with instructions on accessing our course and other relevant information (Garrison et al., 2000). The following day we had our synchronous course introduction (see Appendix C for lesson plan) using Zoom and Mentimeter to reinforce interactions between learners and learners and course facilitators. By employing these technologies in our synchronous session, we hoped to provide our participants with more opportunities to engage in active learning, which researchers Vaughan et al. (2013) suggest may lead to more meaningful educational experiences. A recording was made of this live session to accommodate different student schedules (Lalonde, 2020). For our social annotation 10 activity, we divided learners into teams to facilitate small-group discussions to enhance group cohesion (Vaughan et al., 2013).

Offer support & acknowledgment. Throughout our facilitation week, we provided participants with ample support (e.g., one-to-one virtual support and prompt response to students in email, chat, and discussions) and acknowledgment by expressing agreement and appreciation for individual and collective contributions (Garrison et al., 2000).

Teaching presence. Vaughan et al. (2013) describe teaching presence “as the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes.” (para. 5). As facilitators, this involved setting the curriculum, organizing the course schedule, and also presenting ourselves as “real and there” by participating in the meaning-making that learners were going through (Lowenthal & Dunlap, 2018, p. 284). Some facilitation strategies that we employed included:

Orient students. Right from the start, we wanted participants to feel grounded. Thus, we incorporated multimedia elements — text, images, audio, and video — into the design and organization of our course website (Vaughan et al., 2013). The following lists some components we included:

○ Course welcome message (Fiock, 2020),

○ Land acknowledgment (Lalonde, 2020),

○ Facilitator introductions (Lalonde, 2020),

○ Course description,

○ Course introduction video (Lalonde, 2020),

○ Learning outcomes (Lalonde, 2020),

○ Course schedule with important dates and activity instructions (Richardson et al., 2009, as cited in Fiock, 2020),

○ Required readings and supplemental resources,

○ Contact information, and

○ Virtual office hours to arrange a synchronous chat (Lalonde, 2020; Vaughan et al., 2013).

Send announcements. We frequently connected with participants via email to transfer important information, such as what to expect in the course that week, upcoming events and reminders, and to summarize participant contributions (see Appendix D for communication plan; Lalonde, 2020).

Give feedback. We developed our course to include opportunities for timely facilitator feedback to reinforce learning within our tight timeline (Garrison et al., 2000). However, we wanted to hold back from posting our ideas, clarifying misconceptions, or inserting probing questions as much as possible to allow learners sufficient time to read and form comments on their assigned articles (Watson et al., 2017, as cited in Fiock, 2020). We made this decision because we understood that teaching presence did not mean teacher presence, so we wanted to avoid drawing too much attention to the facilitators’ role to avoid intimidating learners and abating engagement (Vaughan et al., 2013).

Delivery. When it came time to facilitate the course, our team felt it necessary to monitor participant activity and provide support whenever needed. For example, we employed different interventions to address technical issues, adjust instructions, and keep participants on track using various communication methods, such as email, chat, and one-to-one virtual meetings. Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, many participants did not fully engage in our course's main learning event (i.e., the Hypothes.is social annotation activity). Indeed, this hindered participant interaction and impeded cohesion among the assigned student groups for this activity. Around the halfway point of our facilitation week, I became concerned about my teaching presence. Was I engaging too little? Was I meeting the expectations of my learners? If I did not comment on a post, participants might think it was not read. Then again, acknowledging every post could discourage interactions among learners, which would work against the co-construction of knowledge (Vaughan et al., 2013). With little improvement in learner participation and interaction, I increased my presence on Hypothes.is in an attempt to inspire some back-and-forth dialogue. Nevertheless, this, too, did not achieve the desired result.

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

Debrief

This final section centers on my reflections on peer feedback and wraps up with some lessons learned.

Peer feedback. Using peer feedback gathered anonymously from a learning experience assessment, it was clear that our participants experienced the highest level of uncertainty around how our team introduced our social annotation activity and the Hypothes.is tool. While one learner mentioned, they thought Hypothes.is was an "interesting tool" (Anonymous #6, personal communication, October 17, 2022), others felt it was "too cumbersome" (Anonymous #2, personal communication, October 17, 2022) and "not user-friendly" (Anonymous #11, personal communication, October 17, 2022). Furthermore, one participant noted that while it was understood they were to annotate and comment on their peers' posts in Hypothes.is, they were unsure about the expectations around how much and how often they should engage in the activity (Anonymous #6, personal communication, October 17, 2022).

As a team, we could have done a better job of communicating to our participants how valuable their contributions were to the learning of others and how a lack of participation or interaction would result in a course that was not as meaningful or robust. Additionally, to accommodate the needs of all learners, we should have perhaps offered alternatives to those who struggled to effectively use the new technology (Anonymous #11, personal communication, October 17, 2022).

Was Hypothes.is the right choice for our facilitation week? I remain divided. On the one hand, there is evidence that those who could access and use the technology generated some 13 quality discussion. However, one learner felt that introducing a new tool during our facilitation week was "a brave choice due to the learning curve" (Anonymous #10, personal communication, October 17, 2022). Another commented that it might have been "too ambitious" (Anonymous #2, personal communication, October 17, 2022) for a week-long course.

Overall, the learning experience assessment showed that participants' perceptions of our facilitation week were fairly consistent. Most expressed that our course demonstrated strong teaching presence in terms of communication and feedback but lacked significant social presence. Participant comments about cognitive presence noted a good balance of quality resources; however, one learner commented that they "could not dive deeper into them in the time frame" (Anonymous #3, personal communication, October 17, 2022). The most common challenge identified throughout the participant responses was engaging with the course technology. As one learner commented, "I spent more time troubleshooting than actually engaging in the learning through the annotation activity" (Anonymous #4, personal communication, October 17, 2022).

Lessons learned. Despite our facilitation week not being as successful as I had hoped, the experience has helped me explore my role as a course designer and online facilitator and has helped me incorporate meaningful reflection into my work with others. Thanks to the thoughtful insights we received from our peers, it is more evident than ever the need for designers to question why they select a particular technology to use in online environments. They must ask themselves: What is the goal? What improvement will it have on learning outcomes? Moreover, what will our participants gain from using it?

By asking these questions, we can make better selections and enhance teaching and learning. I look forward to transferring all the lessons I learned from this experience into practice as I venture into the world of online education this winter.

In sum, as a graduate student, future learning designer, and someone interested in effective teaching and learning in online environments, this reflection helped me to better understand my professional practice and identify areas of improvement. Were there things I would have done differently? Absolutely! However, I wrapped up this experience with many new insights and knowledge from my co-facilitators and learners. From that angle, you could say that my facilitation experience became just as much a learning activity as the activities my team and I designed for our participants.

Click here to view references and appendix.

Comments