MY PROJECTS

Project | 02

Design challenge | Mobile Mentoring Application

Educational attainment for young adults has lifelong implications for social and economic well-being, health, and other outcomes of individuals (Bonnie et al., 2015). However, a growing body of empirical research suggests that first-generation immigrant secondary students are not receiving the intellectual, social, and emotional support they need to lead successful, fulfilling lives in Canada (Areepattamannil & Berinderjeet, 2013; Busby & Corak, 2014; Kirova, 2001; Lara & Volante, 2018; Vitoroulis & Georgiades, 2017).

The following design pitch aims to provide educators, school administrators, and policymakers with an overview of the challenges that limit academic success among immigrant students in Canadian secondary schools, while offering a solution with results that can be inspiring and rewarding for everyone.

Project | 03

Collaboration Project | A Toolkit for Learners and Leaders Transitioning to Self-directed Learning

The Learning With Purpose (LWP) toolkit has been compiled for leaders who want to assist individuals in becoming self-directed learners, increasing their ability to set goals, stay motivated, and work independently using digital resources and online learning communities.

LWP is a collection of tools geared towards self-directed learning as an instructional approach. It includes an introduction to self-directed learning, a six-step change model for leaders (see slides below), LWP program activities, and targeted resources to develop independent learners.

The LWP program aims to help leaders plan, implement, and evaluate the shift to self-directed learning in their context, while also assisting adult learners in their transition from a traditional learning approach to one that is self-directed.

Project | 04

Collaboration Project | Robots and the Future of Learning: Assessing the Pros and Cons of Humanoid Robots Replacing K-12 Teachers

With robots becoming ever-more ubiquitous in our daily lives, Ashley Breton and Sam Kirk reached out to Hiroshi Kobayashi, Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Tokyo, and creator of the world’s first humanoid robot teacher, to ask him a few questions to better frame their debate on whether or not humanoid robots will replace human K-12 teachers. This lively debate assesses some foreseen advantages, like efficiency and personalized learning, and delves into two contemporary concerns: data collection and algorithmic bias.

What do you think? With the arguments presented in this debate, should humanoid robots replace K-12 teachers?

Presented by:

Ashley Breton & Sam Kirk

Participants:

Hiroshi Kobayashi, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, University of Tokyo

Project | 05

Creating a Quality Digital Learning Resource Evaluation Rubric

Collaboration Project | A Rubric for Evaluating the Quality of Digital Learning Resources

In recent years, the use of digital learning resources has grown, which calls for designers to reflect more on the design of such products. This reflection highlights the need for a reliable evaluation tool, such as a rubric. Our team — Ashley Breton, London Coronica, Emma Keating, and Karen McMurray — engaged in the following five steps to co-create a rubric for digital learning resource evaluation:

1) Explore - Review current literature

2) Aim - Establish the goal of our evaluation tool

3) Determine - Select evaluation domains, performance criteria, indicators of quality, and a rating scale to use

4) Revise - Re-examine the rubric selections and choose only the most relevant for a wider variety of digital resources

5) Create - Finalize the design of our rubric

Project | 06

Making Sense of MOOCS

Collaboration Project | A Critical Investigation into MOOCs

Co-written by Ashley Breton, Emma Keating, Alison Kendrick, and Karen McMurray.

The iceberg analogy has long been used to illustrate that what we can see at the surface is not always what it seems. The same can be said about Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), which Bates (2015) calls “…the most disruptive of all technologically-based innovations in higher education, and as a result… the most controversial” (p. 166). While this statement may seem presumptuous, the early promise of MOOCs led Sebastian Thrun, the founder of Udacity, to famously claim that by 2022, there would only be 10 institutions globally offering higher education (Weller, 2020). While that has obviously not come to fruition, the emergence of MOOCs remains a significant contribution to the educational technology landscape.

BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO MOOCS

A MOOC is a free distance learning program that is designed for the participation of large numbers of geographically dispersed learners via the web (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2016). As stated by Bates (2015), “the term MOOCs was used for the first time in 2008 for a course offered by the Extension Division of the University of Manitoba” (p. 168). The course, Connectivism and Connective Knowledge, was designed by George Siemens, Stephen Downes, and Dave Cormier. They had 2200 students enrolled in its free online version. Later in 2011, Stanford University professors Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig developed the MOOC, The Introduction to AI, which had 160,000 enrollments. By 2021, MOOCs had reached 220 million learners through providers such as Coursera, edX, and Udacity (Shah, 2021).

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

Some of the strengths of MOOCs include: how they deliver high-quality content from elite universities, they are accessible, which allows them to be shared globally, and they force institutions to re-evaluate their attitudes to online learning (Bates, 2015). Some of the weaknesses of MOOCs include: low participation rates, with less than 10% of MOOCs being completed (Murphy et al, 2014), cultural imperialism, where ⅔ of MOOCs are developed in English-speaking countries (Trucano, 2013 as cited in Montbello, 2019, p. 219), and copyright restrictions (Bates, 2015).

CRITICAL RESEARCH PROCESS

Our team chose to explore MOOCs as our technology based on their accessibility and our overall familiarity with MOOCs. Early on, we had discussions about each of our previous experiences with MOOCs, which ranged from one team member having engaged with a MOOC platform without knowing what a MOOC was, to one team member who is currently enrolled in one. While each of our experiences left us with a basic understanding of MOOCs, we felt it was somewhat of a superficial understanding and wanted to expand our knowledge on the deeper implications of MOOCs.

We then engaged in some initial research on MOOCs to become familiar with the current literature, but we agreed that research alone could only teach us so much; we wanted to experience the technology first-hand. We decided to enroll and participate in a MOOC in the hopes that we could make connections to our research. We selected “The Science of Well-Being”, a course developed by Yale University and offered through Coursera, the largest MOOC provider with over 97 million students (Coursera, SEC 2021 Annual Report).

“The Science of Well-Being” was one of Coursera’s most popular courses during the COVID-19 pandemic and is adapted from the “Psychology and the Good Life” taught by Yale University professor Dr. Laurie Santos, who also teaches “The Science of Well-Being”. The course is made up of a series of videos, readings, and a quiz per week for 10 weeks. It also has discussion forums for each week’s topic, as well as ones to ask the professor questions and to give course feedback. A course certificate is available for students who earn a passing grade on each quiz.

Our experience with “The Science of Well-Being” and our initial research began to reveal some interesting elements of MOOCs throughout their history, including how MOOCs have evolved in their design. According to Bates (2014), cMOOCs were the first version of MOOCs and are based on connectivist pedagogy associated with a community of practice and are co-created by participants through the exchange of prior knowledge and experiences. Later, xMOOCs emerged, which are now the most common type of MOOC. xMOOCs are based on behaviourist pedagogy and follow the traditional university lecture-based model. Typically, they are developed by institutions and licensed to MOOC providers, but they are becoming increasingly supported by corporations. For example, “AT&T provided $2 million to Georgia Institute of Technology to fund a MOOC master’s degree in computer science” (Schatsky, 2015, Chapter 4).

The tension to reach profit goals within “The Science of Well-Being” became evident as we progressed through the course. We also took note of the didactic nature of the course, which was exacerbated by the lack of connection points beyond teacher-to-student communication. While there was little connectivism in the course itself, the look of connectivism was seemingly staged with a student audience during the lectures.

Much like the analogy of the iceberg, some of the ways we understood MOOCs before embarking on this journey were above the surface, but our research and experiences have revealed aspects of MOOCs that are below the surface. These aspects have helped us narrow and shape our individual critical issues.

CRITICAL ISSUES

Based on our research, we have chosen to examine the following critical issues in relation to MOOCs:

-

Ashley – The impact of universal design on MOOC learning environments and inclusivity

-

Emma – The factors that affect MOOC completion rates, and how to increase student participation and motivation

-

Karen – How MOOCs contribute to or detract from the democratization of education, focusing on openness.

-

Alison – The relationship between MOOCs and corporate training

As our team continues to comb through the literature about MOOCs and our critical issues, we have developed research questions to help guide us, and have documented our personal observations and learning experiences. As we continue this journey, we endeavour to align our experiences with MOOCs and “The Science of Well-Being” to the current literature with the intention of making meaningful connections to our critical issues.

Project | 07

Implementation Project Plan

Change Management Project | LMS Adoption in Rural K-12 School in Newfoundland

OVERVIEW

This LMS Implementation Project Plan (IPP) places stakeholders at the center by leveraging educational technology to provide a more equitable and engaging learning experience for children in rural communities. According to the Canadian Council on Learning (2006), students residing in sparsely populated regions throughout Canada achieve lower levels of educational attainment than their urban counterparts. Students in rural Newfoundland, where this change is situated, are at risk of widening this gap (Saqlain, 2018). As such, a kindergarten to grade twelve (K-12) school is exploring the potential benefits of a Learning Management System (LMS) to close this gap. To preserve this organization’s anonymity, it will be referred to throughout this plan as Institution X.

This IPP will outline the steps involved in adopting and implementing an LMS to provide opportunities for blended and remote learning to improve student enrollment, engagement, and higher levels of educational attainment at Institution X. The project is expected to take six months, and its success will be measured by the adoption and implementation of the LMS throughout the school. This project does not include how the LMS will be used after implementation. The long-term sustainability of this change will require Institution X to maintain the LMS while seeking opportunities to constantly improve it.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

This chapter is about gaining a better understanding of Institution X, the problem they wish to resolve, and the goals and objectives of this project.

Project Background

Founded in the late 1980s, Institution X is a rural all-grade school with a student population of approximately 120 students and a teaching staff of 15, all of whom commute from three surrounding communities (State of the Nation, 2022a). The mission of Institution X is to “ensure that all students reach their maximum potential through the cooperative interaction of parents, teachers, and students in a safe and caring environment.” (Annual School Development Report, 2013, p. 2).

Institution X has never used an LMS. Over the years, low levels of educational attainment due to a lack of student engagement and declining enrollment rates have impacted student welfare and the growth and prosperity of the region. In 2019, the Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation (CDLI) reported that only 12% of K-12 students within Newfoundland earned credits online (Barbour & LaBonte, 2019). However, the coronavirus pandemic substantially increased electronic learning (e-learning) requirements for schools across the province (Nagle et al., 2020; State of the Nation, 2022b). For Institution X to remain viable and improve its students’ levels of educational attainment, it will need to adapt, prompting the Board of Trustees' desire to select and implement an LMS for the organization.

In November 2021, the Board of Trustees at Institution X consulted with Team B to conduct qualitative analysis to find an effective solution to this perceived problem (Doorley et al., 2018). After making sense of the organization’s implicit and explicit needs, our team assessed Institution X's organizational readiness for e-learning (Breton et al., 2022). Leaders and staff at Institution X shared intent to implement this change and shared the belief in the collective ability to do so (Weiner, 2009). They have since redesigned internal structures, processes, and practices that can benefit from the LMS and ensure the resiliency of the organization (Weller et al., 2013). In January 2022, Team B released a final report recommending the adoption of Blackboard Learn, a centralized learning ecosystem. Team B put forth a set of strategies and recommendations for consideration (see Appendix A).

Scope

This IPP has been scoped to ensure that the selected LMS is adopted and implemented across Institution X. It does not address how Institution X will use this technology to monitor student enrollment, engagement, and levels of educational attainment. In addition, it does not address how students will use this LMS to reach learning goals, how to provide teachers with the training needed to use this tool, or what content and instructional methods to use.

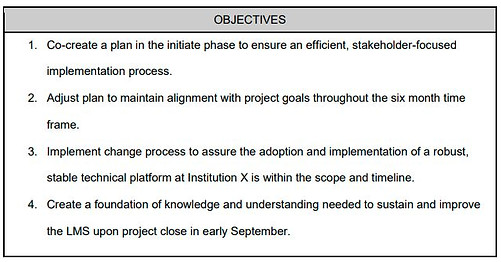

Goals and Objectives

This project will leverage identified LMS to achieve the following goals outlined in Table 1 and five primary objectives listed in Table 2 that follow the SMART format (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-bound) (Breton et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Organizational and Project Goals

Table 2.

Project Objectives

CHAPTER 2: CREATING CONDITIONS FOR CHANGE

This chapter is about 'laying the groundwork' for change (Biech, 2007, para. 25). This requires embedding an understanding of the potential benefits of the LMS solution within the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders and setting a community-wide vision for technology and learning (O’Toole, 2008). If adequate time and consideration are not given to this phase, it may result in low adoption of the LMS (Al-Haddad & Kotnour, 2015).

According to Khan (2017), an adaptive leadership model is the most suitable leadership approach for educational institutions to navigate change, as it involves collaborative problem-solving, flexibility, and the willingness to adjust strategies when internal or external issues arise. By adopting this approach, the project sponsor and project manager will work together to create a shared vision that all members of the three surrounding communities can feel a part of. See Appendix B for leadership actions and behaviours informed by adaptive leadership and ASCEND. Following this list will guide and move this change forward.

Figure 1.

The ASCEND Model

Note: This image is of the ASCEND change management model created by Breton et al. (2022). Learning With Purpose: A Toolkit for Leaders and Learners Implementing Self-directed Learning [Website]. Royal Roads University. https://learningwithpurpos4.wixsite.com/learning-with-purpos

Project Vision

To improve educational outcomes for current and prospective students at Institution X through a thoughtful application of an LMS to promote and facilitate equity and engagement. The core value of Institution X is to “ensure that all students reach their maximum potential” while effectively serving the needs of the community (Annual School Development Report, 2013, p. 2) will play an integral role in this change.

The gap in the current and envisioned state:

-

Current state - Institution X has made minimal efforts to implement an LMS.

-

Envisioned state - The LMS is successfully implemented and adopted across the school.

Closing this gap will require stakeholder groups to work as a collective to transition Institution X to its envisioned state (Khan, 2017).

Stakeholders & Impacts

Stakeholders identified in this change are anyone affected by the LMS implementation (Wagner, 2008 as cited in Kiddler, 2020), including the organization (i.e., Institution X), school administrators, teachers, students, parents, and the surrounding three communities. Each stakeholder group will engage with the LMS differently; therefore, impacts will vary (see Appendix C). These impacts primarily focus on the hard data that LMS learning analytics provide and contribute to Institution X’s ultimate end goal of raising educational attainment among their students.

Team

To ensure this project remains focused, a team of individuals will oversee the LMS transition and drive the change forward. Team B is composed of a project manager and an LMS support manager. In addition, Team B will work closely with a project sponsor, school administrators, as well as other stakeholders and partners (i.e., the extended team). See Appendix D for all project roles and responsibilities. In addition, the LMS vendor will work collaboratively with Team B and the extended team members throughout this project. Open communication between the teams and the LMS provider will be vital and ensure the implementation coordinates with the project objectives and happens within the established time frame (Breton et al., 2022).

Resources

The following resources were identified during the development of this plan:

-

Human capital: Stakeholders with the skills needed to plan, implement, evaluate and sustain an LMS.

-

Policy and funding: Federal and provincial policies and funding initiatives in alignment with e-learning (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Education, 2004).

-

Technology and digital resources: Infrastructure, hardware, and digital content to ensure equity of access.

CHAPTER 3: PROJECT PROCESS

This chapter provides an overview of this project’s general timeline, communication plan, how success will be determined, and suggestions and recommendations for Institution X post-Implementation.

Timeline

The LMS implementation process is complex and will proceed according to the timeline illustrated in Appendix E. The project will initiate in March 2022. It will span six months, with a targeted completion date of fall 2022. Each phase has been outlined according to the Project Management e-book developed by Adrienne Watt (2014). It includes six key deliverables that include:

-

Spring 2022, the project initiates, and conditions for the change are created.

-

May 2022, the change plan and communication plan are developed and implemented.

-

Early Summer 2022, the setup and configuration of basic infrastructure and LMS application are completed.

-

Mid-Summer 2022, the LMS critical functions and customizations are designed to allow for a performance-focused reporting strategy (i.e., learning analytics).

-

Late-Summer 2022, data is migrated to LMS (e.g., courses and content).

-

September 2022, the LMS is handed over to Institution X for live launch.

Communication Plan

Communication is vital for ‘keeping everyone in the loop’ (Watt, 2014, p. 170), and as Biech (2007) points out, it can mean the difference between the success and failure of an organizational change. See Appendix F for the project’s communication plan. The project manager will ensure that stakeholders are continually engaged throughout the change process, so they remain focused on the problem the LMS solution is out to solve (Breton et al., 2022; Weiner, 2009). Stakeholders may not have all the information; therefore specific information will be communicated (see Appendix G).

Success Criteria

The following success criteria were identified during the development of this plan:

-

The project sponsorship was fully behind this change initiative (Prosci, n.d.b).

-

The use and implementation of the LMS are in alignment with the values of the organization and the community that it serves (Gemin et al., 2018).

-

School administrators became early adopters, which encouraged stakeholder buy-in (Breton et al., 2022; Kotter, 1995).

-

Institution X planned and organized LMS training and hands-on practice for teachers to provide support when they require assistance (Breton et al., 2022).

-

Adoption and implementation of the LMS are evident throughout Institution X based on the total number of staff logged into and actively using the system and supports.

Next Steps

The LMS will require continuous maintenance and support even after its implementation. It is recommended that Institution X empower, nourish, and discover (Breton et al., 2022) ways to enhance the system, optimize content, add more courses, and refine the user experience as long as the LMS is in operation. The following are some future considerations:

-

How will new users on the system be trained? (Breton et al., 2022)

-

Who will maintain the LMS post-implementation?

-

How can learning material be formatted to maintain consistency?

-

What will be the permissions for LMS features and data?

-

-

How will Institution X identify opportunities for growth based on current practices (i.e., existing programs, new programs, professional development opportunities)? (Breton et al., 2022)

-

How will Institution X support a learning culture through policies and procedures around content creation and delivery, and the effective use of the LMS? (Breton et al., 2022)

-

Who will develop communities of practice (both in-person and online) for school administrators and teachers to understand research and share effective methods in using the LMS? (Breton et al., 2022)

-

How will Institution X identify ways to promote a culture of LMS best practices through professional development, including training, peer/mentoring programs, and staff recognition and rewards? (Breton et al., 2022)

-

In what ways can Institution X monitor the effectiveness of the LMS transition in the long term? (see Appendix H)

Close Project

Once the LMS implementation process is complete, Institution X is responsible for launching the new system live to stakeholders. Institution X will document any technical issues and report them to school administrators and the LMS vendor. The project manager will celebrate accomplishments and officially recognize team and stakeholder efforts, thank them for their participation, and close the project (Breton et al., 2022; Watt, 2014). A final live meeting will be held for all stakeholders and teams to reflect on the process and share lessons learned to apply to future change initiatives (Breton et al., 2022).

See appendix and references here.

Project | 08

Design Challenge:

E-portfolios for Authentic Assessment

Design Project | Designing for Authentic Assessment

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic forced many higher education institutions to pivot face-to-face instruction online. While education is constantly evolving and changing, this shift has created new professional challenges for educators and intensified the need to adapt how they teach and assess to better support student learning in digital environments.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Our team (Ashley Breton and Katia Maxwell) of secondary and post-secondary educators teaching in production for television and film, and English as a Second Language (ESL), identified adult learning theories and instructional design models to provide the framework for our design challenge.

Our team infused the five phases of the Design Thinking process — empathize, ideate, design, prototype, and test — with the ADDIE model, and rapid, responsive elements of the Agile approach (see illustration here) throughout this design challenge to improve our problem-solving and decision-making capabilities (Bates, 2015a) and to keep the needs of our students at the center of everything we did.

Knowles’ (1984) theory of andragogy and its four assumptions about the design of learning were considered throughout the design process: (1) Adults need to know why they need to learn something, (2) Adults need to learn experientially, (3) Adults approach learning as problem-centered rather than content-centered, and (4) Adults learn best when the topic is of immediate value to their job or personal life.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Working as partners, our design team followed the experiences of instructors and students to design a solution to address this complex challenge by dedicating our efforts to improve online assessment strategies. Using Gabriella, a 25-year-old graduate student, and Ashoka, a 46-year-old college instructor, as extensions of ourselves as we worked through the five phases (Doorley et al., 2018).

Our team stepped in to find a solution that satisfied the needs of both stakeholders. Gabriella and Ashoka are anxious because COVID-19 and the constant threats of pandemic-related hardships have made the sudden transition to teaching and learning online challenging. Specifically, Gabriella worries that her skills and abilities have not been appropriately evaluated and graded in the spring and fall semesters of 2021, but hopes the winter 2022 term will bring a better learning and assessment experience. While Ashoka is looking to make teaching and learning online a more human-centered experience with assessments that meaningfully connect with her students.

From this, we arrived at our problem statement:

Instructors lack an authentic way to support student agency around online assessments to help equip students with the critical skills they need to be successful, independent, life-long learners.

Then, we created our "How might we" statement:

How might we authentically support student agency around online assessments to help equip students with the critical skills they need to be successful, independent, life-long learners?

THE SOLUTION

Employing the authentic assessment model as our design solution to address our problem statement. Together, we reviewed ethnographic research and developed insights and design criteria to generate ideas and appraise the overall purpose, process, and use of an authentic assessment (Weleschuk et al., 2019).

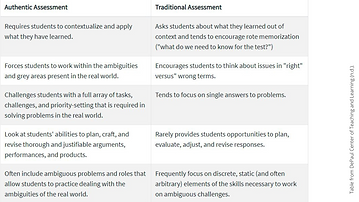

The basis of authentic assessment is on students’ abilities to perform meaningful tasks they may confront in the real world and demonstrate their mastery through the production of digital artifacts or participation in project-based learning tasks (DePaul Center of Teaching and Learning, n.d.) that go beyond traditional tests that tend to over-simplify the learning process (Wiggins, 1990). Table 1 summarizes the advantages of authentic assessment over conventional assessment.

Table 1.

Authentic assessment versus traditional assessment

Note: This table was taken from non-traditional assessment models by DePaul Center of Teaching and Learning (n.d.). This table summarizes the advantages of authentic assessment over traditional assessment.

The general philosophy of authentic assessment is that if an instructor wants to know how well a student can do something, the best way to assess them is to have them do it (DePaul Center of Teaching and Learning, n.d.). Examples of authentic assessment in an online context could be e-portfolios, interviews, role-plays and simulation activities, and so forth. Next, our team identified four pillars or best practice methods for creating an authentic assessment, which include:

1. STANDARDS – Identify the standard knowledge, and skills students need to be able to do to be successful in the field of their context after they complete the course,

2. AUTHENTIC TASKS – Work with university or college faculty to determine how students will demonstrate their ability to do authentic tasks designed or selected for the course,

3. SUCCESS CRITERIA – Identify success criteria to evaluate the task(s), and

4. RUBRIC – Evaluate students’ abilities to complete the requirements of the task(s) using a rubric or other scoring guide (DePaul Center of Teaching and Learning, n.d.; Mueller, 2018; Mueller, 2019).

Upon reflecting on the d.School Bootcamp Bootleg deck (Doorley et al., 2018), we decided to identify one example of authentic assessment to test, rather than arriving at a complete prototype of authentic assessment. We selected an electronic portfolio (e-portfolio) as our assessment tool, which consists of “a purposeful collection of student work that exhibits the student’s efforts, progress, and achievements in one or more areas” (Meyer et al., 1991, p. 60). Through the use of e-portfolios, students would be given an authentic task(s) or desired outcome(s) and collaborate with their instructor to decide on the elements to be assessed, what the assignment would look like, the rubric, and participate in the grading of the final product (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

E-portfolio model as an authentic assessment tool in higher education

Later, our team developed an e-portfolio project by taking it through the four pillars of authentic assessment creation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

After the testing phase, our team concluded that the use of an e-portfolio model to assess students in an online environment authentically offered both of our stakeholders (Gabriella and Ashoka) a collaborative opportunity to create something that not only builds critical skills for the future but promotes deeper relationships and mutual respect between teacher and learner (Morris, 2018). Together, the student and instructor negotiated the assessment design as they decided what would go into the e-portfolio, the elements to be evaluated, the rubrics, and then collaboratively participated in grading the pieces showcased (Weleschuk et al., 2019). These items selected for the portfolio act as evidence of growth, allowing students to become primary players in their learning.

However, for e-portfolios to be valuable assessment tools for digital learning environments in higher education, the long-term commitment to documenting a student’s work over time when constructing an e-portfolio needs to be emphasized above the final product and grade (Mueller, 2019).

This authentic assessment empowers students to reflect on their best work that demonstrates learning derived from experiences that connect to various aspects of their lives, such as personal, school, work, and community (Mueller, 2018).

FINAL THOUGHTS

E-portfolios as tools of authentic assessment offer the best way to support student agency around assessments to provide students with the critical skills they need to be successful, independent, life-long learners.

Through the five phases of the Design Thinking process, we found evidence to suggest they allow students and educators opportunities to “participate fully and meaningfully in technological activities” that make up so many aspects of our lives (Morris, 2018, para. 42). They provide a safe, responsive, collaborative, and empathetic space where learning is “owned by the learner, structured by the learner, and told in the learner’s own voice.” (Hartnell-Young & Morriss, 2006, p. 39). In addition, they allow educators to “teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of students, which is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.” (hooks, 1994 as cited in Specia & Osman, 2015, p. 195)

.png)

.png)